How (and why) to visualize change

I’m not sure how it happened, but art — theatre, composition, visual imagery — somehow became the fringe of the professional world instead of the core. As human beings, our brains fire up and retain vividly when we’re presented with information vividly. But when we erected the scaffolding of assembly-line capitalism and the modern world, we left no room to communicate or explore in a brain-igniting way. We came out the other side of the industrial revolution with Charlie Brown’s teacher as our baseline.

You know this feeling, right? How it is to be presented with an hour-long PowerPoint presentation in a room that feels like all the air has been sucked clean out. Are we inspired, in that room? Are we called to action? Are we ready to consider how things could really be different? All the words in the world can’t describe this feeling better than fourteen seconds of Charlie Brown.

Art is meaningful, sure. In its capacity to move our hearts and minds, it’s a powerful force that can bring more people on-board to important change. And art is playful, which we also like. When art is in the room, the air feels fresher. We feel more engaged, more tapped-in to an elemental openness necessary for important change.

But art is much more than simply meaningful or playful. It is jet fuel for comprehension.

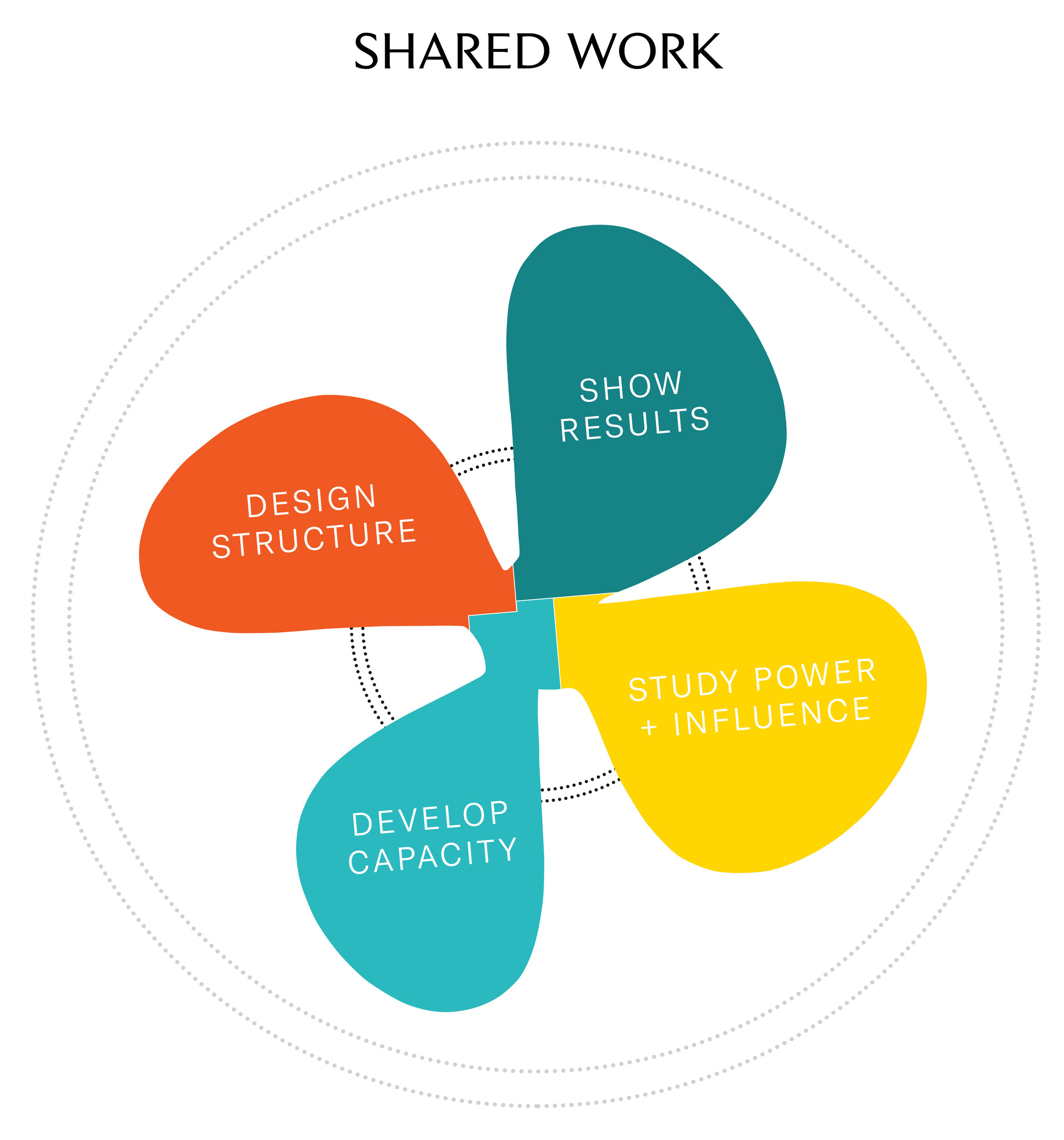

In change work, for example, we are orchestrating and considering layers upon layers of processes, mandates, teams, blocks, organizations, and committees. Without a graphic map of intersections, overlap, patterns, flow, and shared interests, the current reality is very difficult to explain — let alone a new approach for a better future.

The brain doesn’t process bullet points. All the research backs this up: human beings engage far better with complexity when it’s visualized. So as process designers, we have to describe and illustrate what we do.

Right now, Tuesday and I are facilitating big change for highly complex organizations. Each project is a complicated web of relationships, hierarchies, and exchanges back and forth from every angle of what seems like intractable problems and/or impossibly audacious goals:

The International Committee for the Red Cross is re-orienting its global organization for the greatest possible impact in the world’s most urgent trouble zones

Forward Malmö is gathering together several cross-sector NGOs and governmental groups to redesign the city’s systems for a more sustainable Malmö for everyone

The New York Child Services system, an intricate web of professionals within a complicated bureaucracy serving one of the largest cities in the world, is creating an equity and justice-rooted approach to protecting children

An array of organizations who deliver and govern sport in the province of Nova Scotia are collaborating to build Canada’s most accessible, successful athletics and recreation system

Future-making begins with an obstacle map, and traditional reports don’t cut it. Heavy, cumbersome binders full of analysis are too dense for action. Linear instruction is great if you need to know how to build an airplane, but when you’re rolling up your sleeves to backwards-engineer and reimagine something systemic, alive, and relational, you need a map. You need several.

That’s why we work with brilliant mapmakers and designers: to visualize complexity and help us find a way through. We do on-site recording and harvesting with Bravespace to capture how conversations progress, and visualize new revelations and connections as they unfold. Another partner, Bigger Picture, helps us articulate strategy and develop a visual language to give an accessible, at-a-glance view of our progress.

As we gain new insights on theory, pitfalls, and emerging practices of change, we also develop and iterate a curriculum of visual how-to.

Whether it’s live recording or curriculum maps to illustrate key insights, we have a few rules for the most vivid, most brain-igniting visualizations:

1. Make it attractive.

Like a mandala, a graphic concept should draw you in and make you curious. Use colour and pattern to communicate how a scenario might feel — difficult or easy, with a broken flow or good transparency.

2. Make it accessible.

To be a gateway into deeper conversation, remember JEP — just essential parts. Aim for as much crisp, engaging space within the visual concept as possible. Strip away as much as you can. We want to be comprehensive, but remove any redundancies or non-essential clutter.

3. Make it rewarding.

Even when visualizing the challenges or shortfalls of the current reality, show the flip side of simplicity and opportunity. Help people to see themselves — their friction and their aspirations — in the scenario, so it’s provocative and inviting action.

4. Make it surprising.

When we walk by a baker, the scent makes us perk up. That’s how a well-expressed visual concept should grab our attention. This is a big part of my (life / work / belief system / hopes / dreams / challenges). I’ve never seen this presented this way! Bright, provocative visuals are an intellectual stimulant, and they nourish our energy and focus. Especially when they’re a fresh take on a familiar space.

The ICRC alone — just one project — encompasses 18,000 people around the world. How can we invite more of them into this conversation? How can we help them see and contribute to a better future, and how can we help them see themselves in it?

When we visualize well, we help the work of change leave the room. We make sure the progress, optimism, depth, and electricity of an intensive session is carried into an organization’s daily life. Visual recording and language help mark the milestones of a living conversation. They help us be smarter together as we move forward. When it comes to enlisting people in change, good visuals are a rallying cry.